Content from DOIs and Repositories

Last updated on 2024-09-27 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 30 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is a DOI?

- What good is a DOI (compared to, say, a URL), and how do I get a DOI?

- What is a repository?

- How do I choose a repository?

- How do I link GitHub to ORDA?

Objectives

- Understand what a DOI is

- Understand how they differ from other ways to link to your work and how to create and source a DOI for your work

- Understand what a repository is and does

- Feel comfortable selecting a suitable repository

- Know how to link a GitHub repository to ORDA (a DOI-providing repository)

DOIs

Introduction

The code that you write is important. No matter the size, style, or language, it is an integral aspect of the research that it is part of, or indeed, sometimes it is the main output of the research project.

Historically ‘research outputs’ have been focused on papers, and while this is still mostly true, there has been a change in recent years to give better acknowledgement to other research outputs, such as code. There has also been a shift (which we are continuing to see) that funders are requiring other outputs from projects to be made available. While this is mostly focused on the data that has been collected or used, in certain fields code is also part of this. You may also come across conferences or awards that require code to be available (and open) in order to submit or be considered. There’s also been a rich history of code being made free and available to others.

Regardless of the reason you want to disseminate your code, there are some ways you can make this easier for both yourself and anyone who wishes to use your code - these include DOIs, using repositories, providing metadata, and knowing how to cite yourself.

What is a DOI?

A DOI is a type of PID. A PID is a Persistent Identifier - a reference that will continue to identify the same object, person or institution over time. A DOI is a Digital Object Identifier - a PID that refers specifically to a digital object such as an online article, dataset or archived piece of software. Each individual DOI is linked to a specific digital object and (should) always direct to that object, regardless of potential changes to its location or metadata. The most common use of DOIs is for journal articles. A single article should have a single DOI, but they can also be used for databases or software/code.

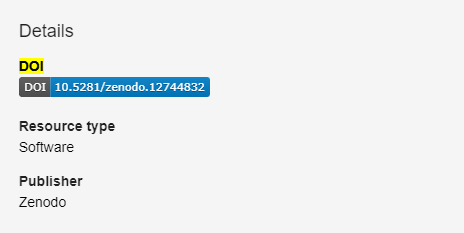

Example DOI

This is what a DOI looks like: 10.1016/j.ascom.2020.100427

You’ve probably seen these many times before because, like this one, they are used for journal articles. Interestingly, the article the above DOI links to is about a tool that has been created, is freely available, and has a licence applied to it, but it provides no link to the code/software itself.

Isn’t that just a link/URL?

No. The internet as a whole is much more fragile than most people think. There area myriad of different ways that things can break or cease to exist. While there are, of course, some old webpages that are still up for no apparent reason, and multiple archives and projects that try to capture parts of the internet (Wayback Machine, Software Heritage), these are by no means complete.

But thinking of your own code, if it’s on a webpage (maybe your own), hosting isn’t free: are you planning on keeping this webpage for a long time? Can you guarantee it will never be moved from that page/URL, and do you know if other people are using that link?

Callout

A DOI essentially makes it someone else’s job to ensure that the link resolves to the right digital object.

Only registered organisations can create DOI’s. To be able to mint a DOI, an organisation must meet the International DOI Foundations standards and pay to become a member, meaning that they must have the ability to ensure the DOIs are maintained.

DOIs are also designed to be short and human-readable, again unlike most URLs, whereas shortened URLs are not persistent.

DOI and version control

Version control is of course very important around code (see the Version Control part of the FAIR24RS training), and you shouldn’t create more than one DOI for a single digital object - however you can nevertheless version with DOIs:

DOIs with multiple versions

That part at the end indicates which version the DOI will resolve to. If you have written some code for a research project, and the current version is the one that was used, but you are still developing it, referencing that version in any paper or outputs will allow people to see exactly what the code looked like at the time the research was conducted.

It’s important to note that if no version suffix is included in the DOI link, it will resolve to the most recent version of the object. This is sometimes exactly what is wanted and sometimes not, so it’s good to think about this when using a DOI.

How do I get a DOI?

To get a DOI for code, the best place to use is a repository. It’s important to note that (currently) GitHub does not mint DOIs. Some examples of repositories that do are Zenodo and the University’s institutional repository, ORDA.

When you make a deposit in a repository that does mint DOIs, there should be nothing extra you have to do, when it has been published, there will be a DOI that you can use to cite and refer to your work.

Key Points

- DOIs are persistent identifiers that should always point to your code.

- They should be maintained by the minting organisation, making them stronger than a URL.

- DOIs can handle multiple versions of the same object.

- Some repositories mint DOIs for deposits.

Repositories

Introduction

Hosting large amounts of data, minting DOIs, creating a usable interface for code and the ability to pull the code to other work setups all takes a lot of time and effort. This is where repositories come in. A repository will make space available to you to deposit your work. GitHub, as a whole, could be seen as a repository, although you also create repositories (repos) yourself inside GitHub. It also does a lot more than just hold your data/code, and of course its main function is version control.

In the last episode we saw some repositories - Zenodo and the University’s institutional repository ORDA - but there are many more out there. Most repositories, certainly used in academia, tend to be fully open, so anyone can access what is deposited.

It’s important to remember this, as you may not want, or be able to, make your code fully open to all (although we encourage you to where possible). However, there are repositories out there that have different levels of access. For example, the UK Data Service repository has three levels of access: open, safeguarded (users must sign the End User Licence), and controlled (users must apply for access with criteria set by the data provider). However, currently the UK Data Service does not hold code.

It’s also worth noting that there are different types of repositories. Some are purely for publications (such as the White Rose Research Online repository), whereas others are data-focused (e.g. Harvard Dataverse).

Differences between repositories

As we’ve just seen, not all repositories are created equal. Some are not just repositories, others aren’t technically repositories at all. This means you should put some thought into which repository you are going to use to deposit your code.

What do you want from a repository

- Do you want your work to be fully open?

- What type of licence do you wish to apply to your work?

- Do you want a DOI?

- Do you need it to handle versioning?

- Do you need your work to be machine-accessible?

You may also need to think about what licence you can apply, as you may be limited by any third party software you are using. This is covered in more detail in the Software Licensing section of this component.

Also the last point is probably more important around data rather than code.

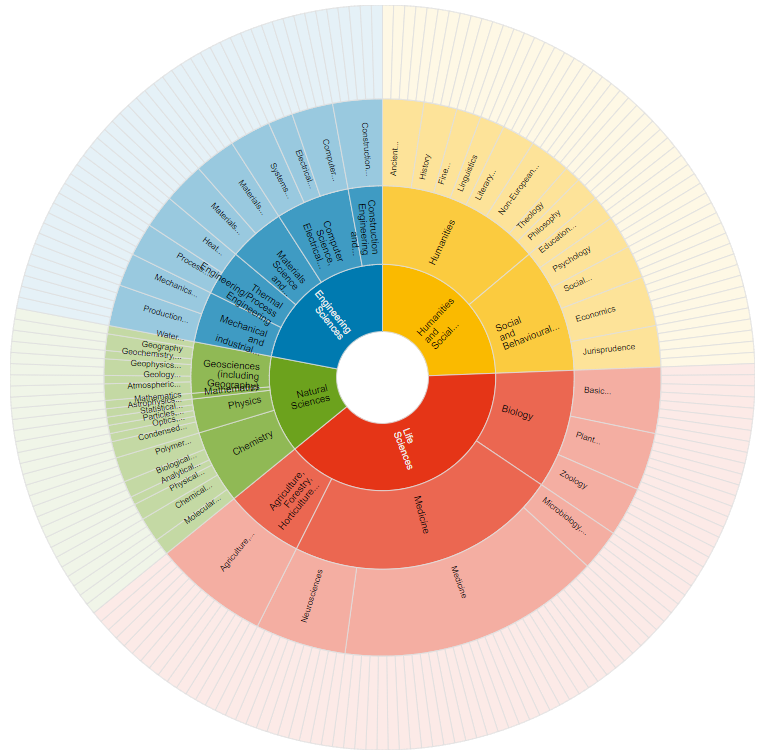

Choosing a repository

As there are many different repositories out there, choosing a suitable one for your code is an important task. You may know the repository that you wish to use already, or you may wish to find a suitable subject-specific repository. Both re3data and FAIRsharing hold a directory of repositories that can be browsed, searched, and filtered to help you find the most suitable repository for your needs.

Both have a useful description of each repository and helpful icons to enable you to quickly answer some of the questions listed above.

Our own guidance is that you should look for a subject- or data-type-specific repository first, and if nothing is suitable or has the functionality required, then you should use ORDA (the University of Sheffield institutional repository).

Challenge 1: Would making my code a package be better?

If one of the main aims is to make the code you have written more (re-)usable by others, would it not be more suitable to create a package of the work, and what would be the pros and cons of doing so?

Think about who ‘owns’ packages, how they are disseminated, and what we wanted to achieve with our code

Maybe! But also probably not. The main issue is that they are different things really, or at least help and aid in different ways, but use a lot of the same vocabulary. While a package will most likely make it much easier for people to use you work (a simple install command), it often doesn’t make it more citeable.

For example, the main repository of Python packages - the Python Package Index or PyPI - holds over half a million projects, but does not mint a DOI for these projects. However, recently, all R packages on CRAN have been attributed a DOI. Now of course there’s differences there in how packages are regulated, but it’s a good step forward in giving the creators of packages the recognition they deserve.

This is also the issue with using just GitHub that while it holds all your work, and enables people to access, read, use, and reuse your work, it also does not mint DOIs, as its main function is to aid in version control and allow a team to work on the same project at once. Therefore, unlike other repositories, it is not so concerned with the long-term storage or archiving of work , and, while nothing has happened yet, it’s also worth remembering that GitHub is owned by Microsoft and could technically change at any time.

You can learn a lot more about packages in the FAIR24RS component on this topic, including how to create and publish your own and how to automate the publication.

You may also consider the fact that while usually it is good practice to only put your work in one repository, it might be beneficial in this instance to have a package created for easy download, and also place your work in a repository that grants a DOI for better citation. (Note: it’s bad practice to gain more than one DOI for an output).

Can this not all be automated and made simple?

There are certainly things you can do to help you manage this, but it depends on your definition of simple.

Within ORDA, you can link your account and your GitHub account.

Challenge 2: Go to ORDA and find the button that imports from GitHub

See if you can find the button for linking a GitHub repo in ORDA

We’ll go through this in a minute, but if you did actually find it, well done! Figshare (of which ORDA is an instance) does a lot right, but has some very strange decisions inside it as well.

ORDA

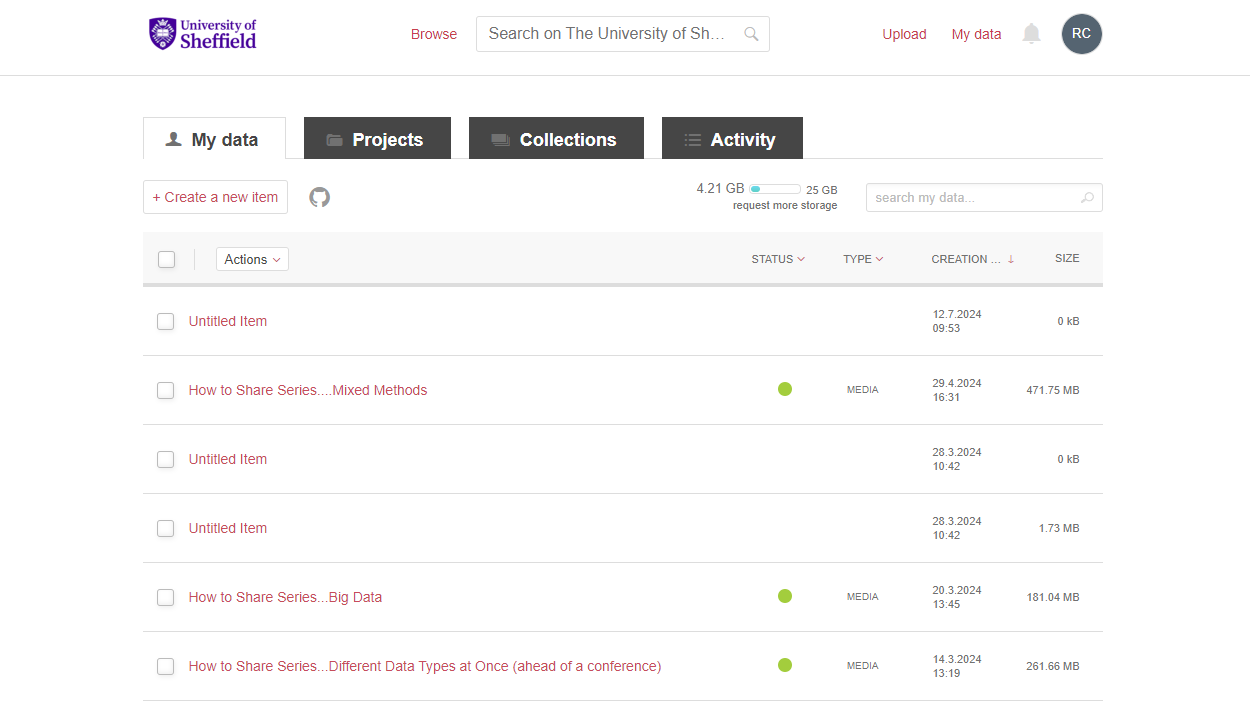

This is the ORDA landing page, showing my login. All University of Sheffield staff and PGRs should have an account to access ORDA as it is associated with your staff/student profile (N.B. it is also deactivated with your profile if you leave, but can be reactivated for a period if needed to allow a deposit or edit to be made).

From here, if you go to the My Data section in the top right, you will see something like this:

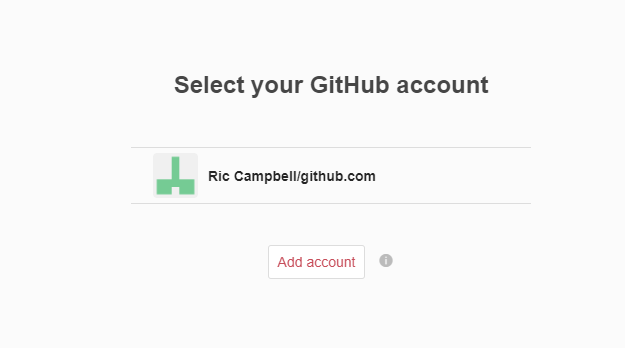

You might be able to see it now, but it’s still not clear how useful that button is. Next to the ‘+ Create a new item’ button is a greyed out Octocat. Hovering over this will fill in the colour and provide the helpful words ‘Import from GitHub’. Clicking on the icon will give you this popup:

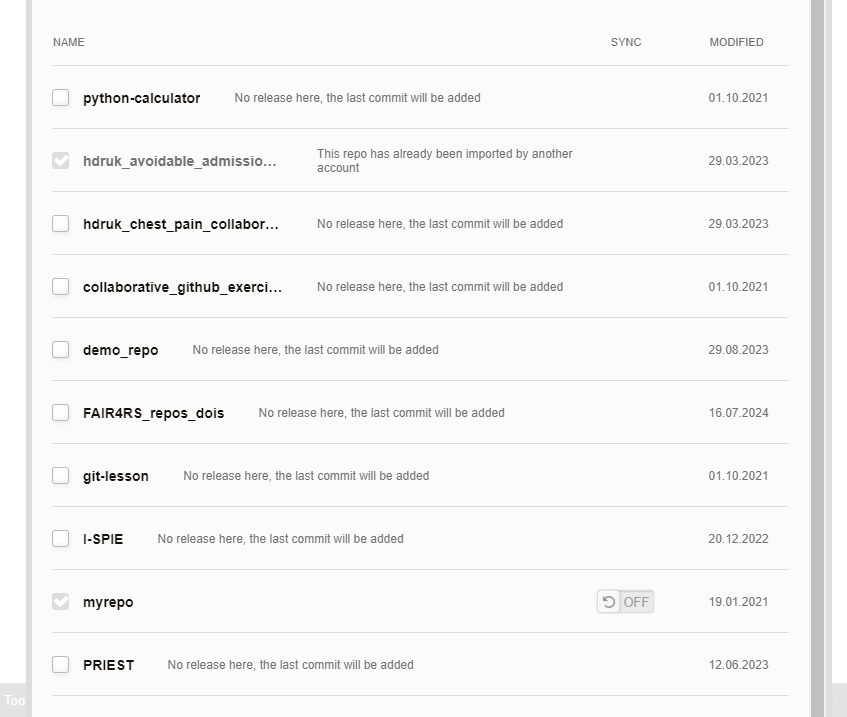

And from this you can link your account, and pull in a repo directly to ORDA. You can see from the image below that it simply allows you to select which repo you want to pull across.

There are a few other bits of interest in this image as well. First, you can see that if a GitHub repo has been imported by another user, it doesn’t let you create another deposit for it (remember, this would mint another DOI for the same output), and this is across all instances of Figshare (for example that one is in the main Figshare.com instance). There is also a simple option that you can see there that allows automated updates of your GitHub repositories to be pulled into ORDA: the slider between the repo name and last modified date.

However, that automation is reliant on the use of a GitHub Action, which might not be the best approach for you (guidance on the Action).

Alternatively you could use Figshare’s API to automate the creation of a new version. There’s a much more detailed description and example of how to do this in the Packages component of this course.

As mentioned above, if you are thinking of having both a package in a repository, and depositing somewhere else to get a DOI, this is something you give good consideration to, as they may be extra work to ensure that there are not different versions of your work in different places.

Zenodo

Of course, these are not the only places you can use. Similarly in practice, you can deposit a GitHub repo in Zenodo. GitHub provides guidance on how to do this.

Key Points

- There are numerous repositories available and you should consider what you want from one

- Some are better than others depending on your purpose and needs

- GitHub doesn’t mint DOIs, but you can link your GitHub repos to a repository that does

Content from Metadata and Citation

Last updated on 2024-09-27 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 15 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What is metadata and why is it important, and what is best practice around metadata?

- What does good metadata look like?

- I can cite/people can cite my code?

- What do you want people to access if it’s cited?

- How do I cite code?

Objectives

- Understand the role and need for metadata for your outputs

- Know what best practice is and be able to apply it

- Learn from examples of good metadata

- Understand the importance of citing all work

- Be able to think about what should be cited

- Know how to cite code, and how others can cite you

Metadata

Introduction

Simply put, metadata is data about data (hence meta). This might not be that helpful a description however, but is necessary as it holds true across all types of metadata. If we continue with the idea of depositing your code in a repository as we saw in the previous episode, however, it becomes much clearer. The metadata is the data that’s on the deposit ‘front’ page, so to speak. It is there to inform anyone who comes across the deposit what they have found without them having to dive too far into the actual data or code.

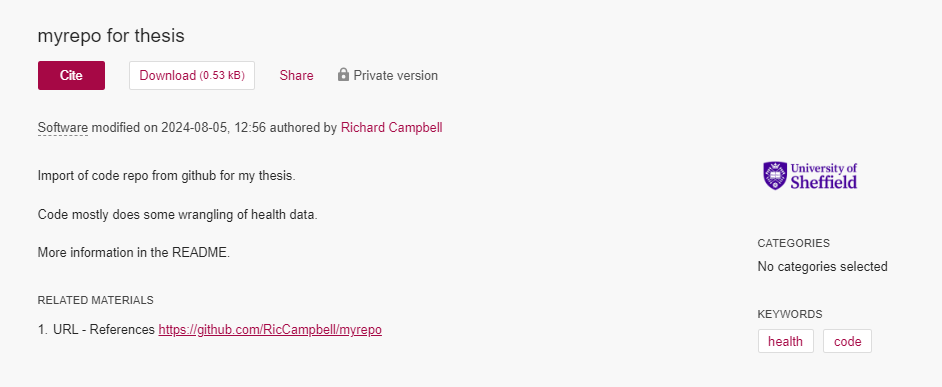

Can you show me some good metadata?

Of course, however, it might be more interesting to look at some bad metadata, as it’s probably more effective in showing how important metadata can be.

As you can see there, there’s some information about the deposit, but it’s probably not nearly enough for anyone to know what it really is, or if it’s useful to them. This code could be perfect for someone to use, or adapt, but they wouldn’t know without having to do a lot of work to figure this out. There is a link to the GitHub repository, but that’s probably not got any more information in it, and still, as we’ve seen, that wouldn’t enable someone to reference your work. (N.B. There’s no DOI on this deposit, as it’s just a draft - we wouldn’t really accept a deposit into ORDA that had so little information - another good reason to think about metadata, as ORDA isn’t an outlier in this regard).

But there is a README there, which asks the question:

Is a README metadata?

It’s a good question, and one I’m sure people would argue over as they have different views on it. Technically, metadata is for finding software, while documentation, including READMEs, are for understanding it. However, the thing that actually matters is that you should probably have a README, and metadata, and other documentation as well. READMEs and other documentation (comments etc.) should be created early and updated as you go along, with potentially metadata being created later in the lifecycle. However, a good README may directly feed into your metadata. There’s no problem with copying and pasting elements; in fact it can be beneficial: it saves you time, and makes sure everything is consistent.

It might be worth thinking of metadata as the overarching information about your code. A README goes into more detail but covers the whole software/project, and comments etc are much more fine-grained documentation relating to the places in the code where they reside.

There is a Documentation module on this FAIR24RS course, which goes over all things documentation in more detail.

Challenge

What metadata do you think should be included in a deposit?

Think about what you might want to see if you were reusing code (i.e. a package), or what you probably take for granted that you know about your code

- Name (a good one)

- (Lay) summary

- A description of what it is

- What language is it in, and versions

- Provenance

- It’s licence (see licence section)

- Any related material

- Dependencies

- File structure

These might not even be everything depending on what you have created. You might want to have use cases, the target audience, key features, compatibility etc. The point is to have information that reduces the workload or thought that someone has to take on in order to know what it is they’re looking at, and if it’s useful to them.

None of these are world-changing ideas, but they do require some thought:

Callout

“There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.”

– Phil Karlton

You may have heard or seen this quote before, but it does stand true: naming things is hard. This principle is normally applied to variables, but it does carry over to other elements too. Creating a short, informative summary or description can be tricky, but doing that using no specialised vocabulary makes it harder, as does trying to include all the less tangible, or overarching, elements that you know about your work but others do not.

If we go back to the example of bad metadata that we saw earlier, there are actually two bits of information there that are helpful.

- It’s got the right type of item type selected, as it’s down as ‘software’, which makes it easier for people to find and know immediately what it is.

- It also mentions that it’s mostly to do with ‘wrangling of health data’. This is not much information, but it can be very easy to forget the most simple elements. If you’ve only ever worked with health data and written plenty of bits of code to help, you might not think to mention this very high-level piece of information.

Machine-findable

It’s best when thinking about creating metadata that you think of human users. It’s also really good to think of yourself as one of these users, either yourself a few years ago, when you might have known less of the area and might not have known exactly what you were looking for, or yourself in a few years, when you’ve most likely forgotten everything about this code, why you made it, and what exactly it does.

However, you also get a bit more findability for free by creating metadata, as these fields are often used and standardised for machine readability as well.

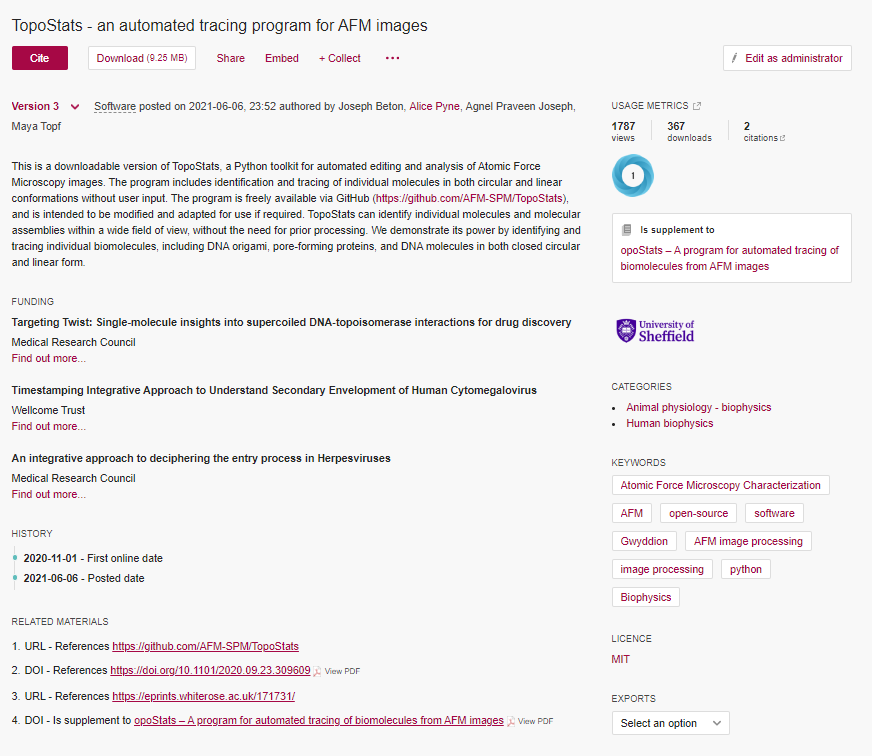

A good example

We’ve seen a bad example, but what would a good example look like?

Can you pick out the good (and bad) elements of metadata in the above deposit?

- Author names

- Version number

- Date created

- Item type

- A clear name

- A clear description

- Licence

- Categories and keywords

- Related materials including a link to the relevant paper

- Initialism in title (bad)

There’s also the language that it is written in, both in the description and the keywords. The first three listed, names, version, and date, would all fall under what was previously referred to as provenance. As you can see, a lot of these are fields you probably have to complete when making a deposit to a repository, which makes it easier, but if you are taking a different route, these could be easy to miss out. It’s also important that you keep these items up to date if they change. Do also take a bit of time to consider them - for example, it’s not good form to miss someone off an author list, and this applies to software author lists as well.

Standards

As we’ve just seen, a repository, even a GitHub repository, has fields for some of this information and these will be implementing a standard, but if you are adding metadata that isn’t a standard GitHub/repository field, or creating your own metadata document, you might need to consider using a standard for your metadata. Some examples are schema.org’s SoftwareApplication type, and CodeMeta. These help tools to work with your metadata by having a set standard. For example if you created it now, what would you call your author list field? Possibilities might be author_list, authorList, developer, developers, writer, creator, coders etc., are all these synonymous with each other for everyone? Would you complete those fields the same for your project? Implementing a standard stops this from happening, each field has a precise meaning and information on how to complete/read.

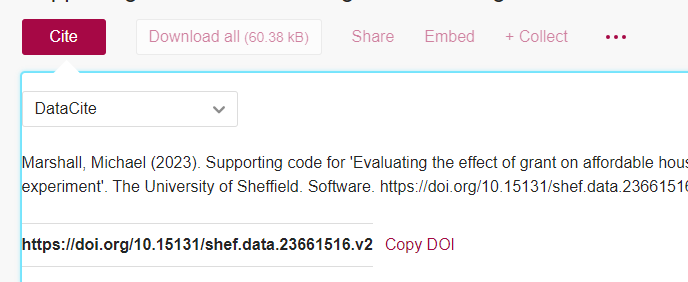

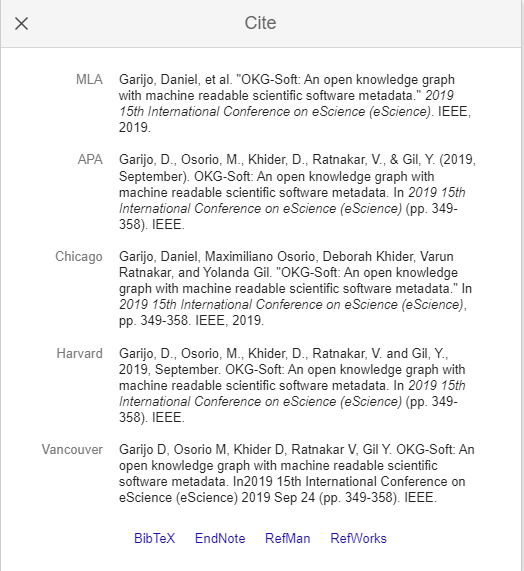

You’ll have come across standards before, of course, when you download citations of papers for your reference manager software:

Key Points

- Metadata helps drive discovery of your software

- It’s easy to not include key elements as these are ‘obvious’

- Standardisation of metadata is useful to help tools use the metadata

Citation

Introduction

If we go back to the first thing that was stated in this module,

The code that you write is important. No matter the size, style, or language, it is an integral aspect of the research that it is part of, or indeed, sometimes it is the main output of the research project.,

This also applies to code that other people write. That’s why it’s important to know that you can (and should) cite other people’s code when you use it, and also how to enable other people to cite yours.

DORA, funders, and the (hidden) REF

DORA, The Declaration on Research Assessment, sets out to improve the ways in which the outputs of scholarly research are evaluated, essentially moving away from a focus on the impact factor of journals that you publish in. The University of Sheffield is a signatory of this declaration. DORA prompts institutions and the sector as a whole to consider different ways of evaluating research quality, including assessing the quality of all research outputs (e.g. datasets, code) as well as published journal articles, and encouraging recognition of all authors’ contributions.

We’re also seeing a continued movement from funders to make open and available all aspects of research projects as the importance and cost of all elements are more fully recognised. For instance, we’ve seen this with data, with a lot of funders requiring (where suitable) this to be made openly accessible, and we’re also increasingly seeing it with code. Making things open and reusing existing work are both important goals, and ensuring people get the recognition they deserve from their work is essential (and also in most cases a legal necessity - see licence section of this module, or software Terms and Conditions e.g. SAS).

There’s also been some movement with the REF as well, with more types of outputs being considered eligible to be returned, and if we think about impact case studies, a useful piece of software could easily have a substantial impact. There are also movements like the Hidden REF, whose objective is to gain recognition for all people who contribute to research, and are also wanting institutions to pledge to making 5% of their REF returns non-traditional research outputs (i.e. anything that’s not a journal paper or book).

These are also all good reasons not to simply cite the associated paper for a piece of software (if there even is one), but to cite the software itself - and to make it easy for others to cite your own code.

Citation and CITATION.cff files

Citation of software is of course different to that of a standard journal article. Normally there is one version of an article and nothing that can really ‘break’ with them; this is not true of software. Also, a paper tends to have all the information you need to cite it correctly quite clearly there for you - again, this often isn’t the case for software.

Challenge

Think what people might need to know from a citation to be able to reproduce a piece of research. (I.e., to make sure they’re using the same piece of software used in the original study?)

Some of the main things to know about the software used that would be integral to being able to reproduce the outputs would be:

- Title

- Authors

- Version used

- Where to find the software

- How to access the code (if different to the above, and available)

The first two, while it’s clear that they should be part of a citation, might not immediately seem relevant when thinking about reproducibility, but if you think that they can sometimes act as a kind of ‘primary key’ to help people know they’re working with the right software (see the last episode and its discussion of naming things).

The bottom three you can see would be needed in order to be certain you can reproduce the work as best as possible. We know that many changes can happen between versions, some big changes, some small changes that could have knock-on effects to how everything works. Of course, where to find the software goes back to our first episode, and having a solid pointer to the code can be solved by getting a DOI for your work (you should of course not mint a DOI for other people’s work, and you might just have to cite the best link available).

CITATION.cff files are designed to pull together

everything you or others need in one place. Similar to README, or

LICENCE files, they are top level files that contain in a standardised

fashion all the information required.

This is an example of a CITATION.cff file (the one for

this module):

This CITATION.cff file was generated with cffinit.

Visit https://bit.ly/cffinit to generate yours today!

cff-version: 1.2.0

title: 'Software dissemination and impact'

message: >-

If you use this software, please cite it using the

metadata from this file.

type: software

authors:

- given-names: 'Jenni'

family-names: 'Adams'

email: 'j.adams@sheffield.ac.uk'

affiliation: 'University of Sheffield'

orcid: 'https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2420-0763'

- given-names: 'Ric'

family-names: 'Campbell'

email: 'r.j.campbell@sheffield.ac.uk'

affiliation: 'University of Sheffield'

orcid: 'https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0975-9270'

repository-code: 'https://github.com/RicCampbell/FAIR4RS_repos_dois'

url: 'https://github.com/RicCampbell/FAIR4RS_repos_dois'

abstract: >-

While putting your software online certainly helps it satisfy the FAIR principles, simply doing so might not be enough for other researchers to actually find and utilise what you’ve put out there.

It’s important to know the benefits and issues with where you store and publish your data, and to make the most of the tools these platforms provide, such as Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs). It’s also important to know best practice for how to increase the visibility and citability of your work in cases where your chosen platform lacks these features.

This course will introduce and explore worked examples of elements that you should consider when publishing your software, which will help you easily reference your work, and also help make it more findable and reusable by others.

keywords:

- carpentries

- fair4rs

- university of sheffield

- repositories

- dois

- metadata

- citation

license: CC-BY-4.0As you can see, this has all the relevant metadata needed for full citation, and you can see where it was created. This has also been updated manually as well when things have changed, but there are lots of places online where you can see the fields needed and the style they should be in if you have a quick search.

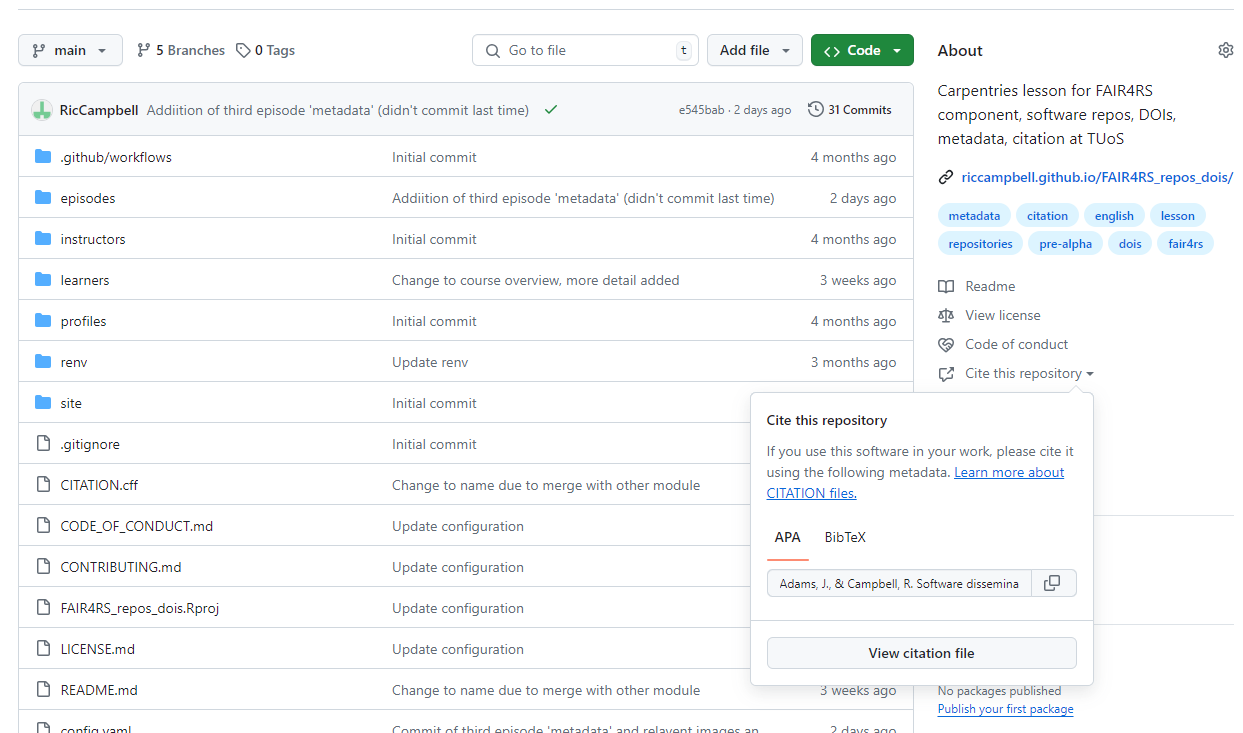

If this is inside a GitHub repo, then on the right hand side, you will be able to get the citation text, or download one to be imported into a reference manager, via a BibTeX file.

So this is great for people citing your work and for getting the correct information to cite other people’s work.

Not all citations are created equal

GitHub is not the only platform to make use of

CITATION.cff files; however, not every platform or

repository uses them either. As previously mentioned, you can link your

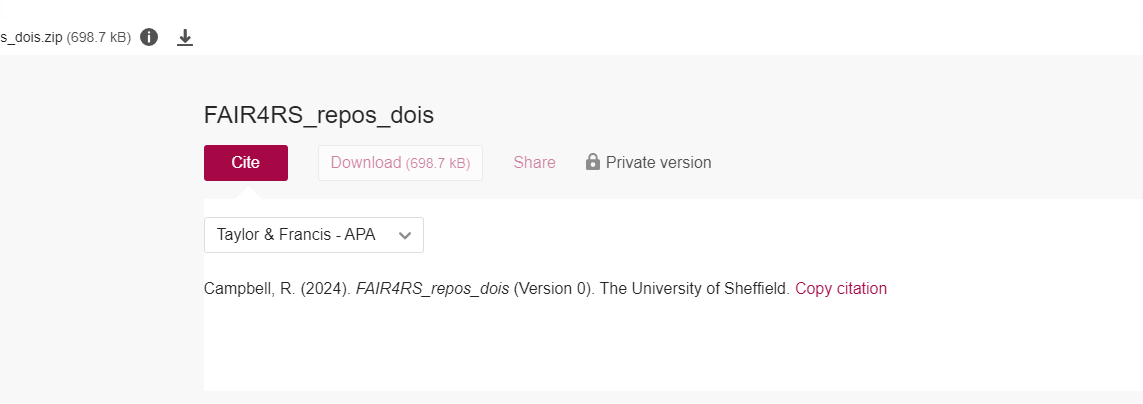

GitHub repos to ORDA, the University of Sheffield repository, and ORDA

has an easy way of creating citations as well:

However, the two citations that we’ve just seen for the same output

are not the same. The issue comes with the fact that Figshare (which the

University of Sheffield repository, ORDA, is an instance of), does not

look in the CITATION.cff file, but instead creates one from

the metadata that is entered for the deposit. In this example, the

author list is different as I’ve entered all authors into the

CITATION.cff file, but have not edited this in ORDA. It’s

easy to add these, but it means repetition of work. While this isn’t

ideal, it’s important to try to get everything the same where possible.

You don’t know where your work may end up once it’s been made open, so

controlling what you can to start with really improves chances of the

provenance being kept with it, and the ability of people to find the

original repository. The CITATION.cff file should also

always be kept with your work if it does get shared onwards, and helps

to this end as well.

GitHub citation:

Adams, J., & Campbell, R. Software dissemination and

impact [Computer software]. https://github.com/RicCampbell/FAIR4RS_repos_dois

ORDA citation;

Campbell, R. (2024). FAIR4RS_repos_dois (Version 0).

The University of Sheffield.

Extending your CITATION.cff file

There are also a lot of standardised fields that you can add to your

CITATION.cff file, other than the ones we have already

seen. You can link to a related journal article if there is one, or you

could cite a dataset that is contained in your GitHub repo. For more

information about these extensions, GitHub provides an easy-to-follow help

page on the subject.

Key Points

- Citation is important to ensure that the correct recognition and credit is assigned to all work

- Citation of software differs from that of articles, but is needed to aid the reproducibility of work

-

CITATION.cfffiles should contain all the necessary metadata and help create citations for use. - You may need to complete the relevant fields in multiple places to ensure correct citation in all cases.